Synopsis

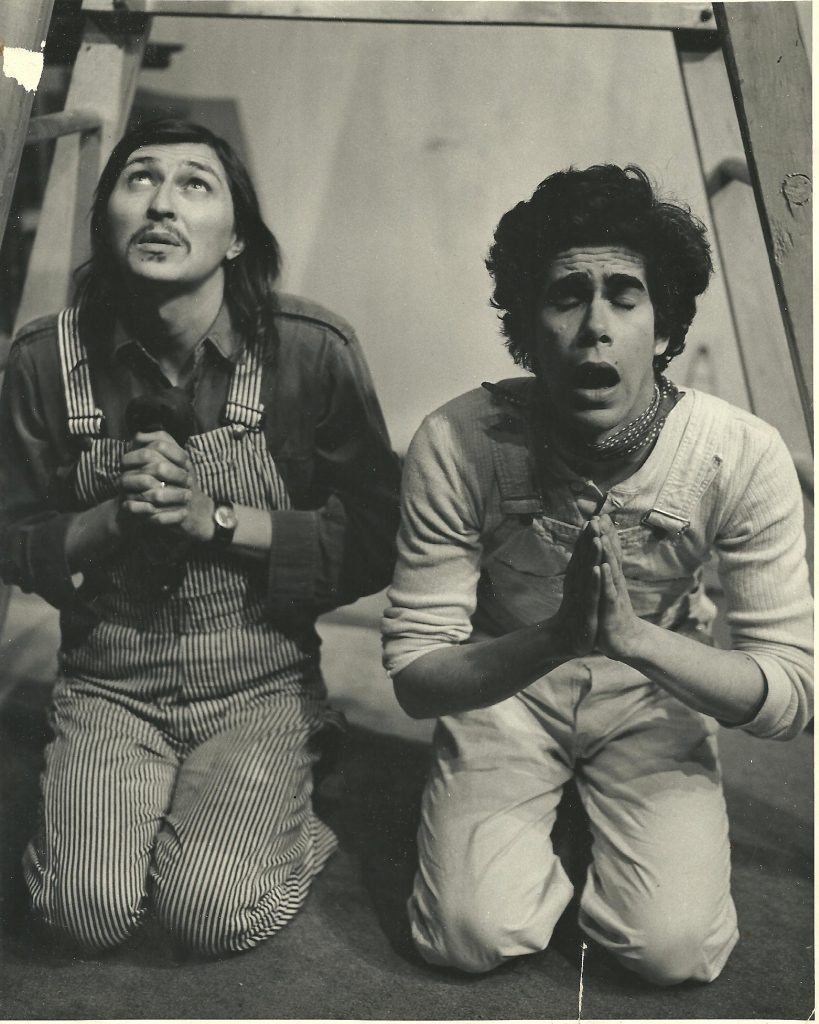

The people have decided to build a tower that will reach all the way to Heaven. Near the top of the construction are a Worker, enthusiastically hammering away, and a Smoker, who’s stopped to take a break and is sitting back and questioning the validity of the whole project: why are they bothering, if they’ll eventually get to Heaven the natural way anyhow? What will they say to God when they get there, and what will he say to them? The two argue, agree, disagree, engage in a praying competition – and then, communications begin to break down…

Critical Responses

“A really fine peace of comic invention… They converse in the general manager of Beckett’s Estragon and Vladimir, had these been a comedy team.”

– Lloyd Dykk, Vancouver Sun, April, 1972

“There is an extraordinary amount of humour for such a sacred subject… Lazarus is exploiting a dazzling middle game in theological chess.”

– Keith Ashwell, Edmonton Journal, March, 1975

“Luckily, Babel Rap is not written for theology majors. It is written for anyone with a sense of humor that is willing to use it… A comedic performance of surely biblical proportions.”

– Samantha Wu, Mooney on Theatre, 2019

Production History

In 1972, John belonged to a small Vancouver theatre company called Troupe. They were putting together an evening of short one-acts written by the actors in the company, and they needed one more show to fill out the evening. John challenged himself to write a play on the next thing he saw, and he looked up and saw the lighting technician’s stepladder. He went home that evening and wrote Babel Rap, to be performed on a stepladder that would represent the massive Tower of Babel.

After their successful run with Troupe, the play was transferred to a downtown Vancouver theatre called City Stage. Soon after that, it was anthologized in a book of short Canadian plays, and went on to become the most-produced Canadian play written up to that time. It has been translated into French, Hebrew and German, performed all over the world, and anthologized in several play collections. In 1977, one production of the play by an Ontario church youth group was cancelled by their minister on grounds of blasphemy, and another production by another Ontario church youth group was presented by their minister as the Sunday morning sermon.

Requirements

Two actors of any gender, one setting (an oversized stepladder), one act of 30 minutes duration.

Excerpt

SMOKER: But I still don’t understand what happens when we get there.

WORKER: I’m sorry, but I still don’t understand what the hell you’re talking about.

SMOKER: Okay, look. We arrive. We look around. We see the angels and the pillars and the gardens of flowers. Hooray! Whoopee! We’re in Heaven!

WORKER: Right!

SMOKER: Yeah, well, then what? What do we do then? Have lunch? Go sightseeing? Start another tower?

WORKER: Well – uh – we could do whatever we want to, I suppose. Personally I’d sort of like to just gaze upon the countenance of the Almighty.

SMOKER: Yeah – that’d be nice. But you wouldn’t want to do that forever. For one thing, it’d be rude. You don’t just walk up to the Almighty and gaze upon his countenance, like some gawky tourist. You’d want to say something.

WORKER: Well, sure! A private audience with the Almighty Himself!

SMOKER: What would you say?

WORKER: Well – I’d introduce myself – and I’d introduce you – and I’d tell him how happy I was to be there.

SMOKER: Yeah, but he already knows all that. He knows who we are. He knows that you’re happy to be there and that I’m happy to be there.

WORKER: I know. But it’s just a way of being polite. You know? Making conversation?

SMOKER: Well, maybe he’d take offense.

WORKER: Why should he take offense?

SMOKER: Well, you’re sort of talking down to him, telling him stuff he already knows. What if he says, “I already know all that. Tell me something I don’t already know.” Ha! That would stop you, wouldn’t it?

WORKER: Oh – he wouldn’t do anything like that. He’s too polite.

SMOKER: You never know. After all, he does work in mysterious ways his wonders to perform. Nobody really knows what the rules are. Something that’s polite to you or me might be very rude to him. Look. Suppose you say, “Good morning, God, how are you?” That’s pleasant enough, right?

WORKER: Sure.

SMOKER: Yeah, but he’s the one who decides whether it’s going to be a good morning or not. So your saying “Good morning” could be taken as a very presumptuous command.

WORKER: Oh, now –

SMOKER: Not only that, but if you ask him “How are you?” you’re implying that he’s changeable; that he isn’t perfect. He could have you up for blasphemy just for saying hello.

WORKER: Why are you being so negative?

SMOKER: Because I don’t think anybody’s thought this whole Tower business through properly. It might make him mad. What if we arrive and he says, “What the hell is the matter with you wise guys? Why can’t you die like everybody else?”